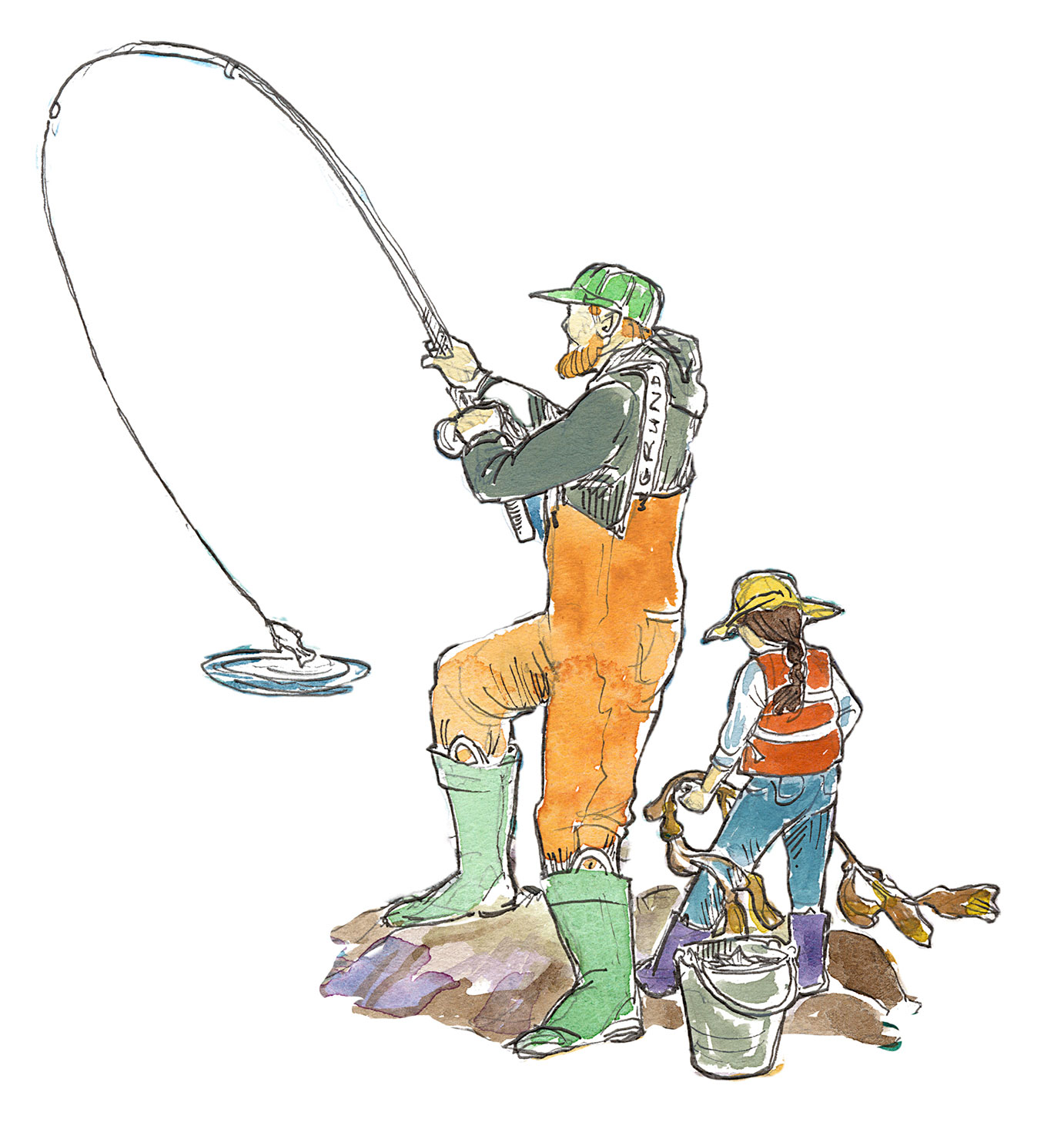

Who Lives Here?

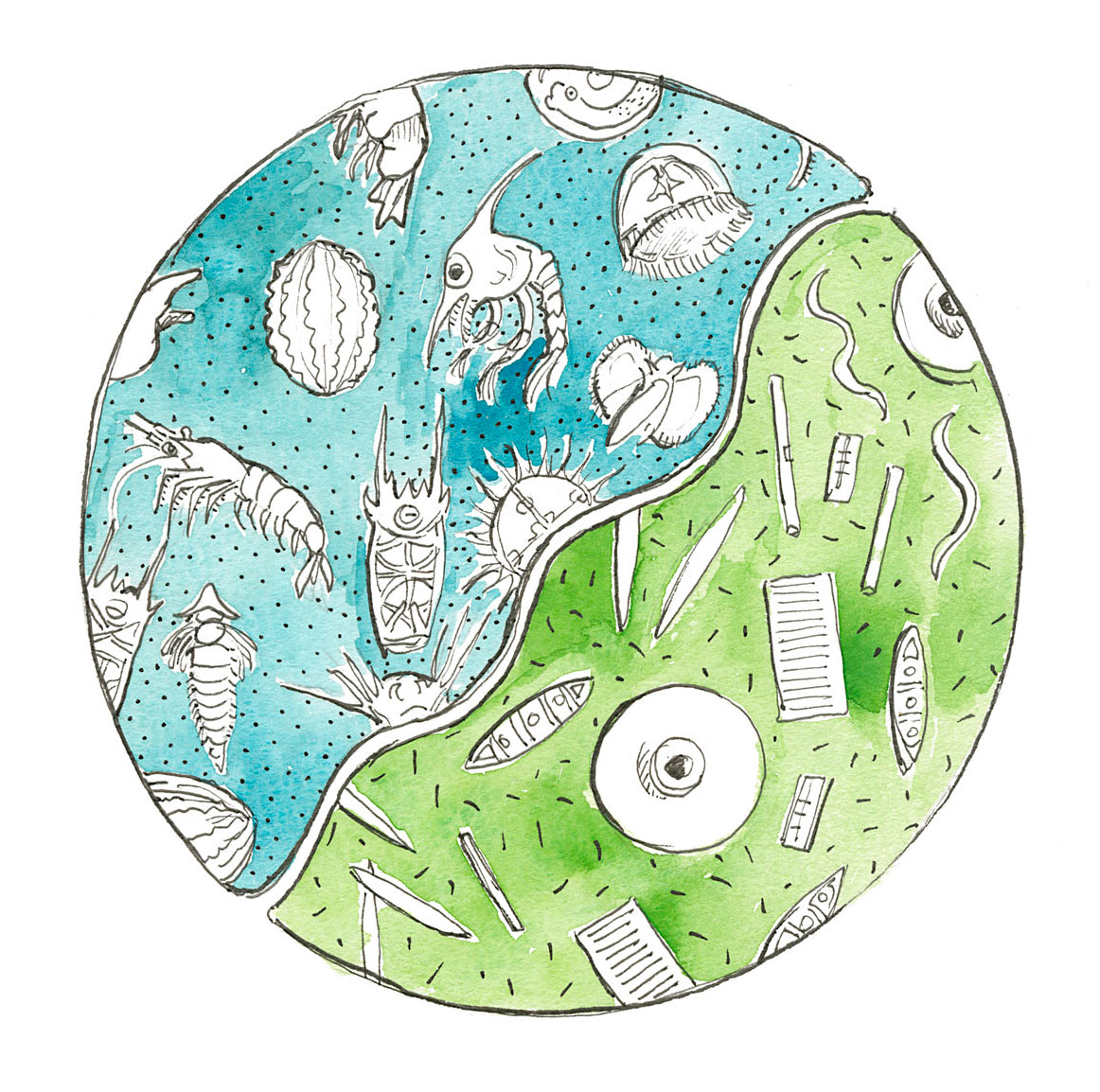

Olympia oysters grow on a variety of shoreline materials as well as in deeper nearshore waters. They can grow on rocks, sandbeds, pebbly beaches, shell mixed with mud, or other hard surfaces like pier pilings, riprap, old shells, or structures put out by groups interested in increasing the hard substrate for oysters to grow on. These surfaces are often surrounded by squelching, boot-sucking mud. It is not easy terrain for people to explore. But it is a rich and productive world. The illustration introducing this webstory paints a vibrant picture of this richness. There is a lot going on. Dive into the details of the illustration and meet ten species woven into the Oly’s world. This is a tiny subsample of estuarine biodiversity, but these ten organisms, from tiny plankton to large herons, can point us towards understanding what a healthy Bay looks, feels, and sounds like. We humans are an integral part of this biodiversity. Work researching and designing Olympia oyster, eelgrass and other estuarine habitat restoration projects plays an important stewardship role, boosting Olympia oyster numbers and the recognition of this tiny but mighty mollusk. The stories of these interwoven characters are a drama about the future vitality of the Bay itself.