A Colorful History

1800 – 2025

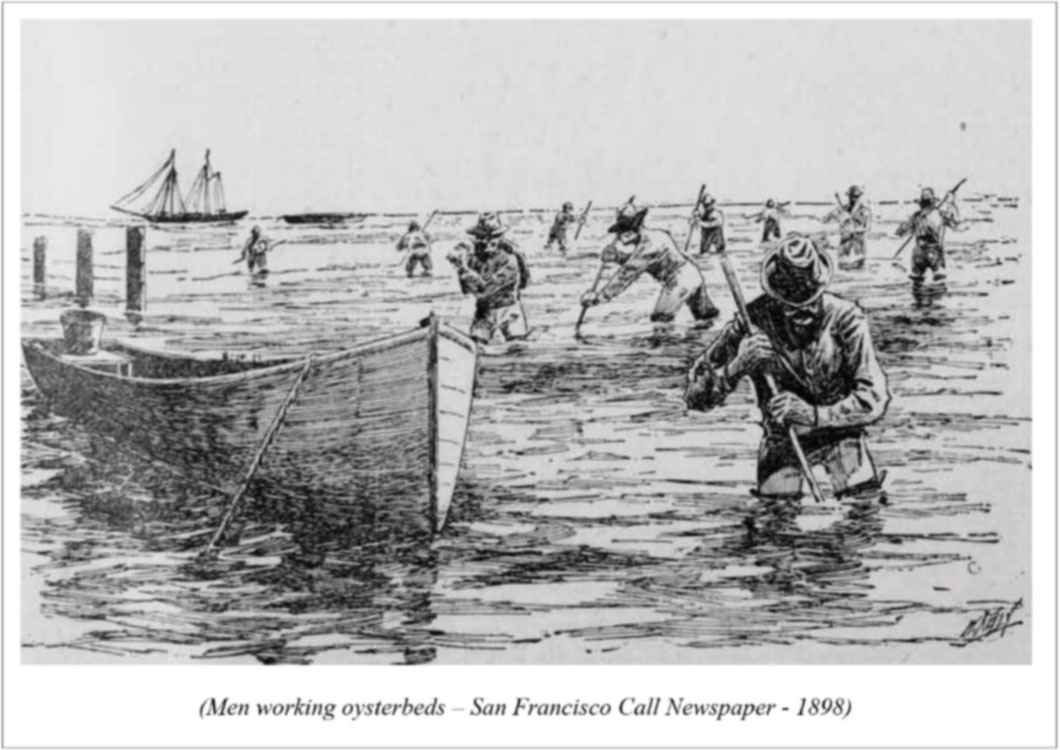

The San Francisco Bay was created at the end of the last ice age, filling with melting glaciers and rising seas. The Olympia oysters, eelgrass, adjacent organisms, and estuarine fishes moved into this zone protected from the rigors of the open coast. The remarkable productivity of life spreads at the margins of the Bay, where free-floating plankton harness the energy of the sun, turning plant matter into protein— serving as the conveyor belt of health for all sorts of aquatic animals. Juvenile salmon come down from the rivers into the Bay before going out to the ocean, and other fish come from the ocean into the Bay to reproduce. Young fish grow quickly in these fertile waters. Olympia oysters also found their needs well met: plentiful phytoplankton to fatten and grow on, water just warm enough for reproduction and salty enough to be happy, and enough hard substrate to attach to and establish a layer of their own kind to create the underpinning of oyster beds underwater and along the edges of the Bay.