A Place Where Land, Rivers, and Ocean Mix

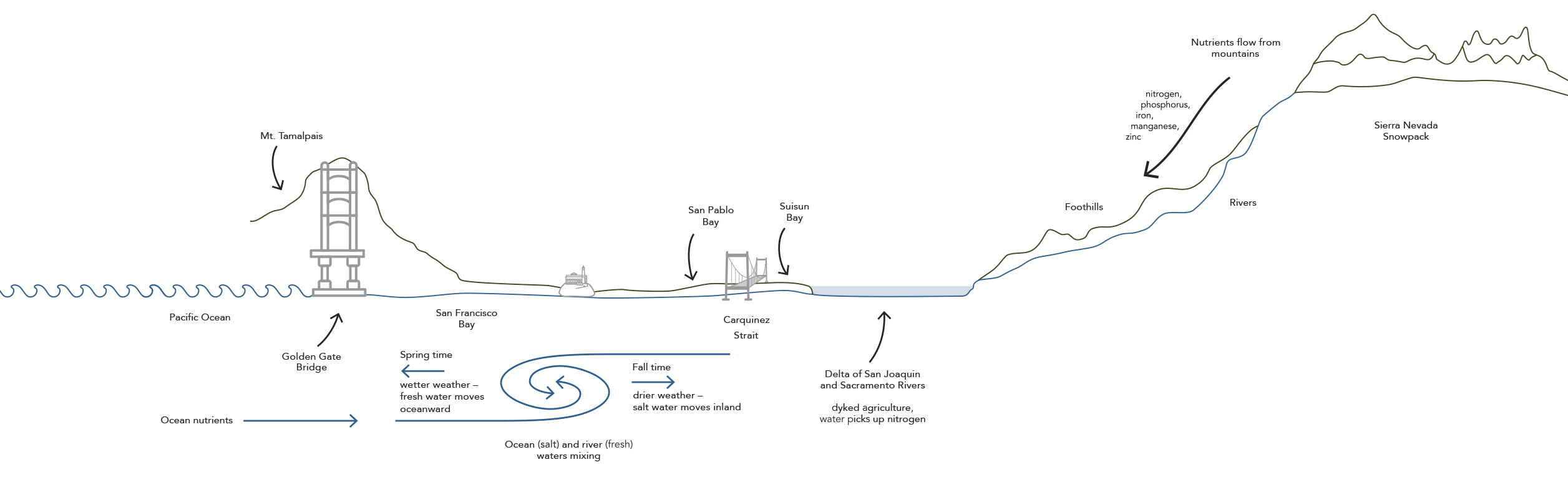

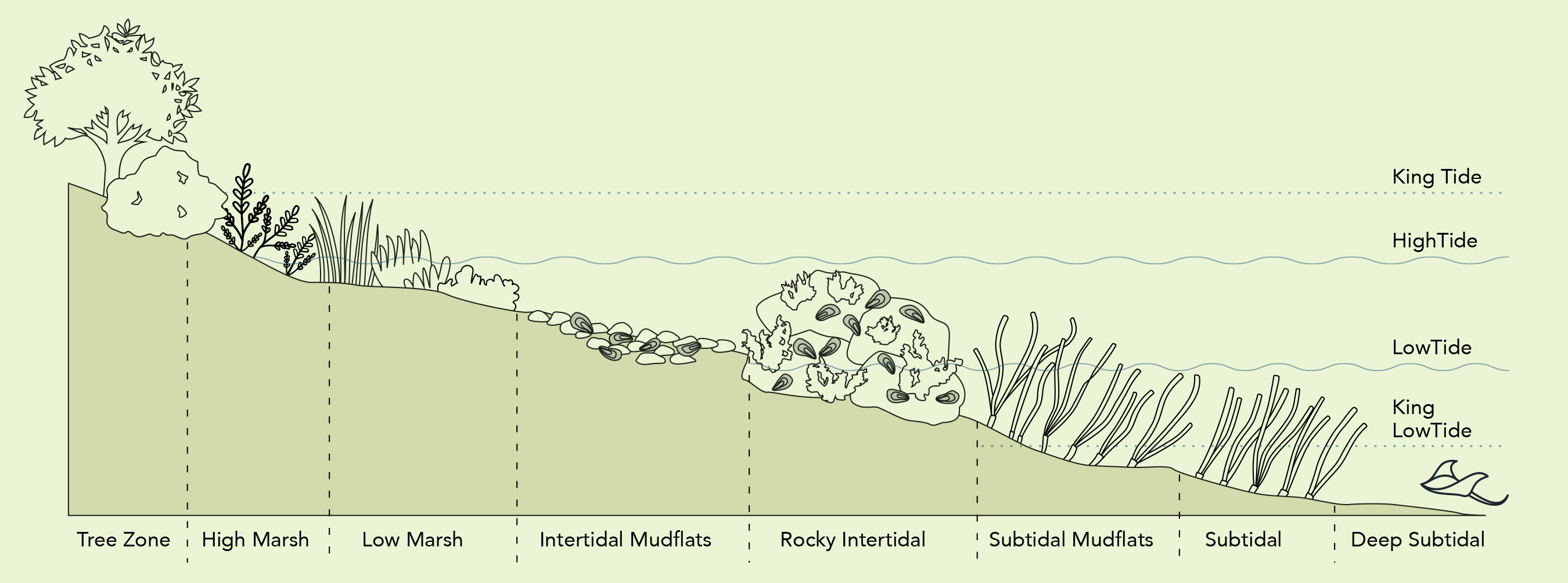

Estuaries are where rivers come from higher elevations and enter the ocean realm, mixing their nutrient-rich fresh water with the ocean’s salty water. Estuaries are where the ocean enters into terrestrial territories meeting river water in tidal pulses, pushing brackish, salty water into marshes of cordgrass, bringing ocean nutrients into tidal mudflats, oyster beds, and eelgrass meadows.

The San Francisco Bay-Delta is one of the most dynamic and remarkable estuaries in the world. It is where the Sacramento River, originating from the north and fed by the American and Yuba Rivers, and numerous tributaries, joins the San Joaquin River from the south, fed by the Stanislaus, Tuolumne, and Merced rivers coming out of the high Sierra Nevada mountains, and flows to the sea. The Pacific Ocean, in turn, comes through the narrow Golden Gate, bringing deep-water upwelling nutrients from the offshore Greater Farallones Marine Sanctuary into the Bay with each 6-hour cycle of incoming and outgoing tides. These waters are pushed up past Alcatraz and Angel Island into the North Bay towards the Delta, as well as south into the shallow waters of the South Bay.