Why More Olys?

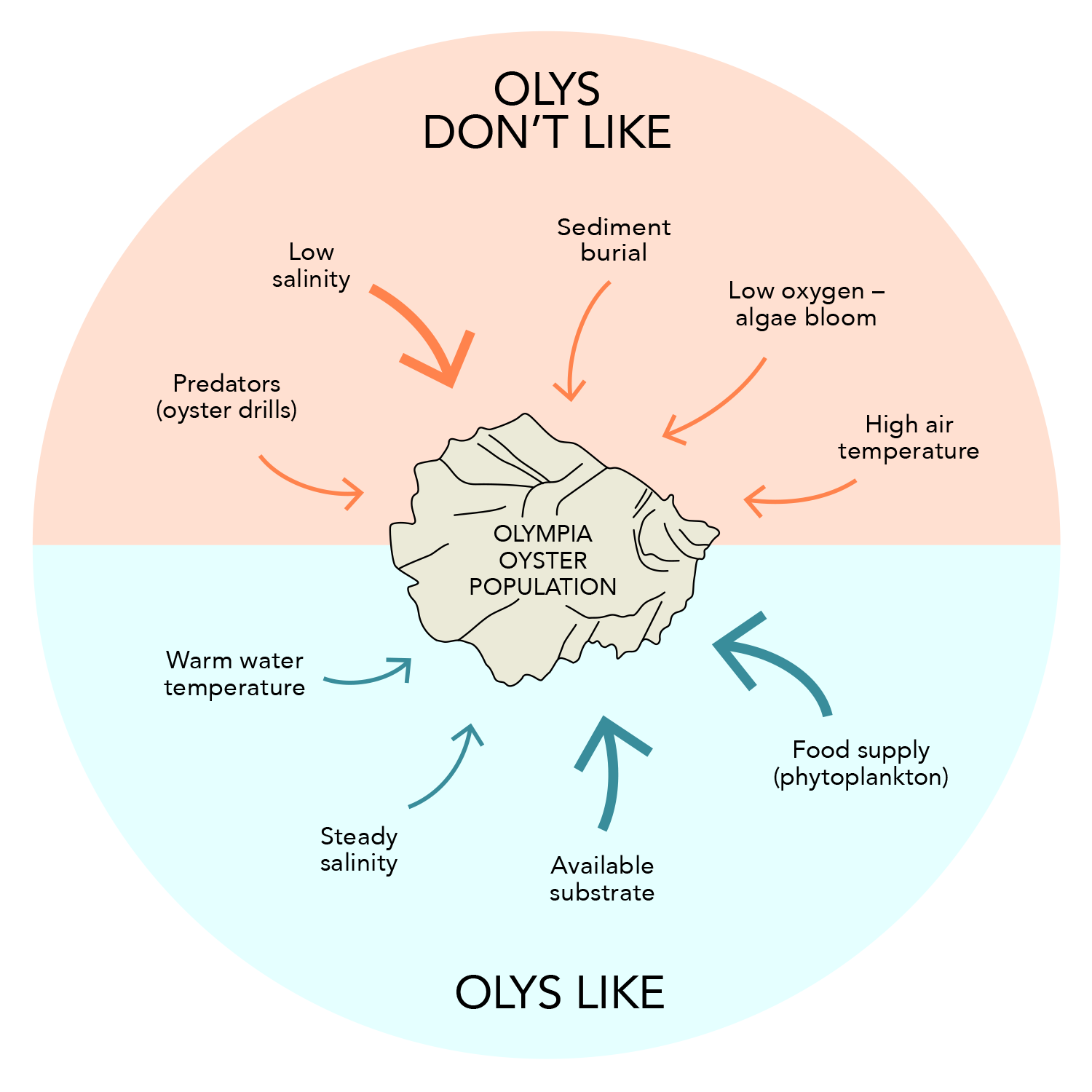

Supporting Olympia oyster populations in the San Francisco Bay is, at heart, about the greater health of the Bay. Cleaner, clearer waters in the Bay will support Olys, and rebuilding the Olympia oyster habitat will support a healthier, more productive Bay.

It is confirmed in paper after paper, survey after survey, and generally among ecologists around the world that oysters are hugely beneficial to the water and organisms around them. Olympia oyster beds create habitat, especially for small invertebrates, and promote larval settlement and general biodiversity, creating a feeding ground for ducks, crabs, fish, and so much more. These oyster beds are an iconic native estuarine environment that has been missing for way too long. The pilot projects restoring Olympia oysters in the San Francisco Bay—which have involved a remarkable partnership of Bay stewards—make clear it is worth the effort to rebuild this Oly world.

Though Olys process less water than their larger cousins, they filter the phytoplankton and other particles in the water directly around them, a bonus for nearby eelgrass and other primary producers that need light to grow. New experimental evidence makes clear that when Olympia oysters are in proximity to eelgrass the ecological functions are greater than when Olys or eelgrass are alone. The surrounding mud itself is more productive, and stores more carbon, and more fish are around. The resilience of these mixed shoreline communities—its diversity and its defense against rising sea level—increases.