Is it Mom or Dad?

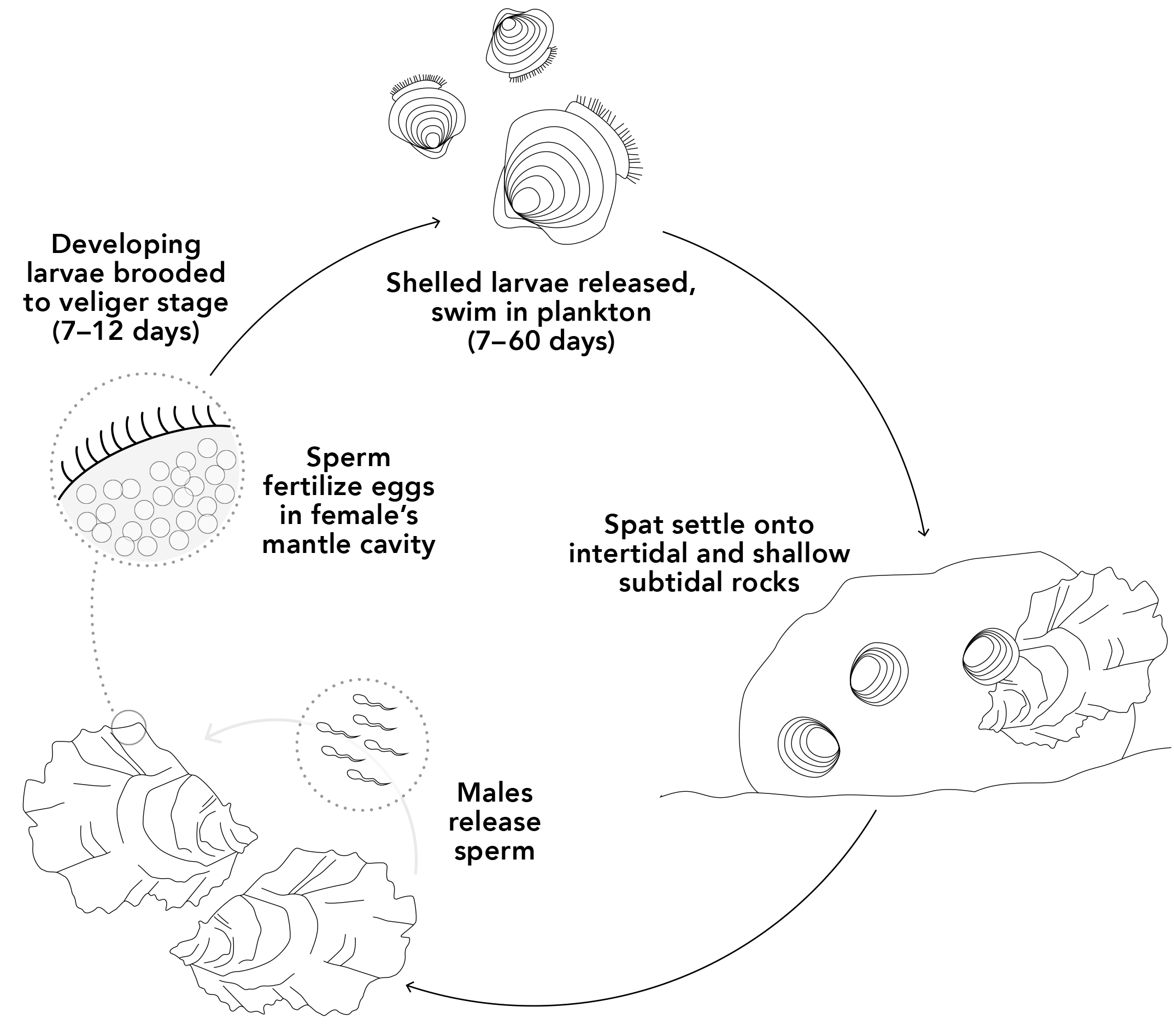

The Olympia Oyster Life Cycle

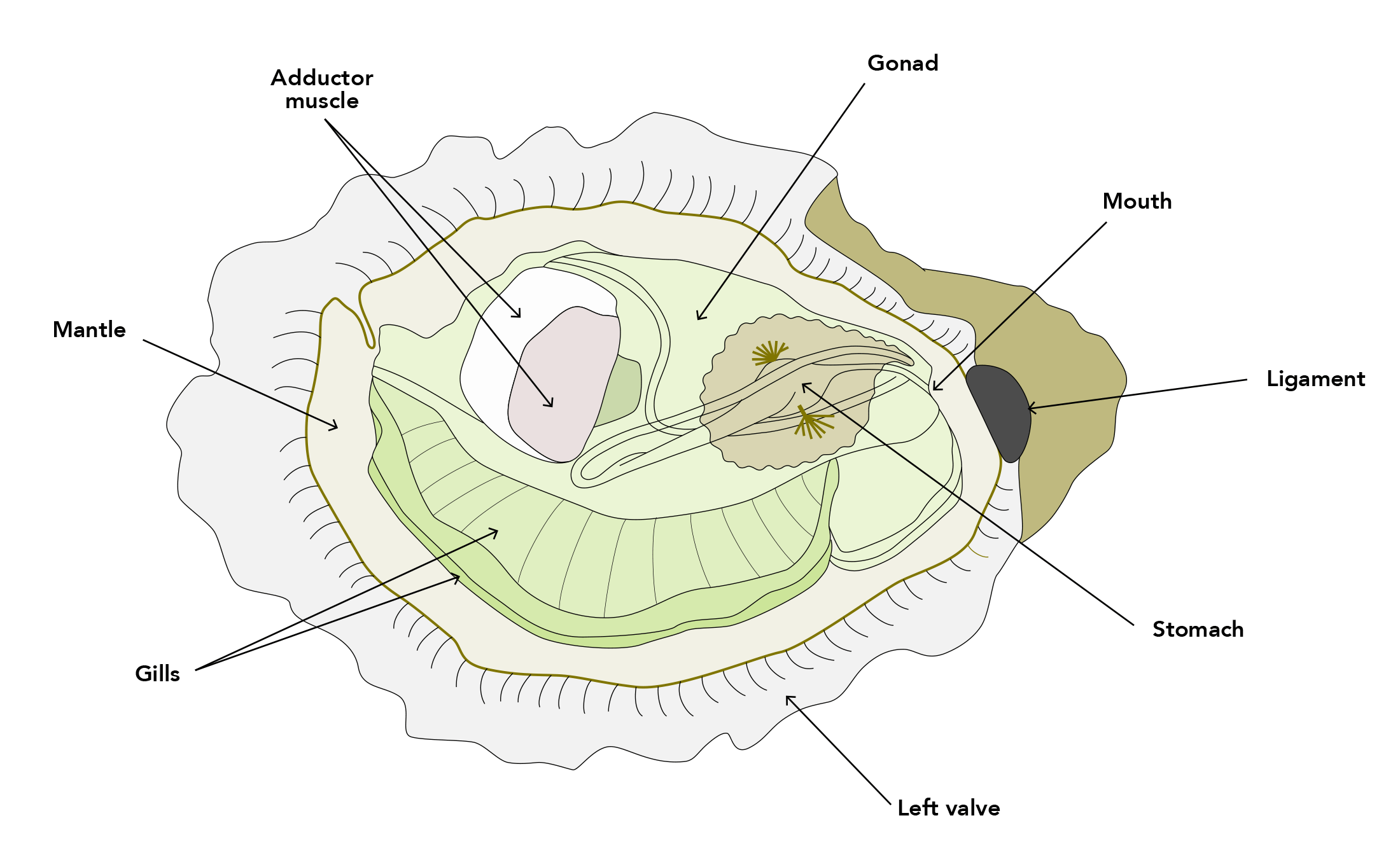

Like many other organisms, oysters make both male and female gonads and can change their sex. After starting life as male, and a first broadcast of sperm at about five to six months old, an Olympia oyster will then change sex regularly, being both female and male numerous times throughout its life. This, theoretically, keeps an ample number of males and females nearby for successful breeding, and ideally, different age classes will be represented in a given Oly bed. Females of many oyster species also broadcast their eggs for chance fertilization in the water column, but the female Olympia oyster and other Ostrea moms bring the sperm into their shells with respiratory action and fertilize them internally. The fertilized eggs then develop within the shell and start their own shell building…inside the mother Oly! In about ten (7-14) days, when the larvae are expelled into the surrounding waters, they already have a tiny shell, an advantage one would think when entering the wide world as estuarine plankton, oyster larvae.

As soon as seven days or as long as eight weeks of drifting, Oly larvae, if they haven’t been eaten, will use chemical cues to find a surface to settle on (often the underside of a surface!) and metamorphose into the sessile, fixed-in-place bivalve. The newly settled oyster is called “spat.” The extended time the larvae spend floating with currents means that children often settle far from their parents, ensuring a mix of genes in each community of oysters that finally settle.

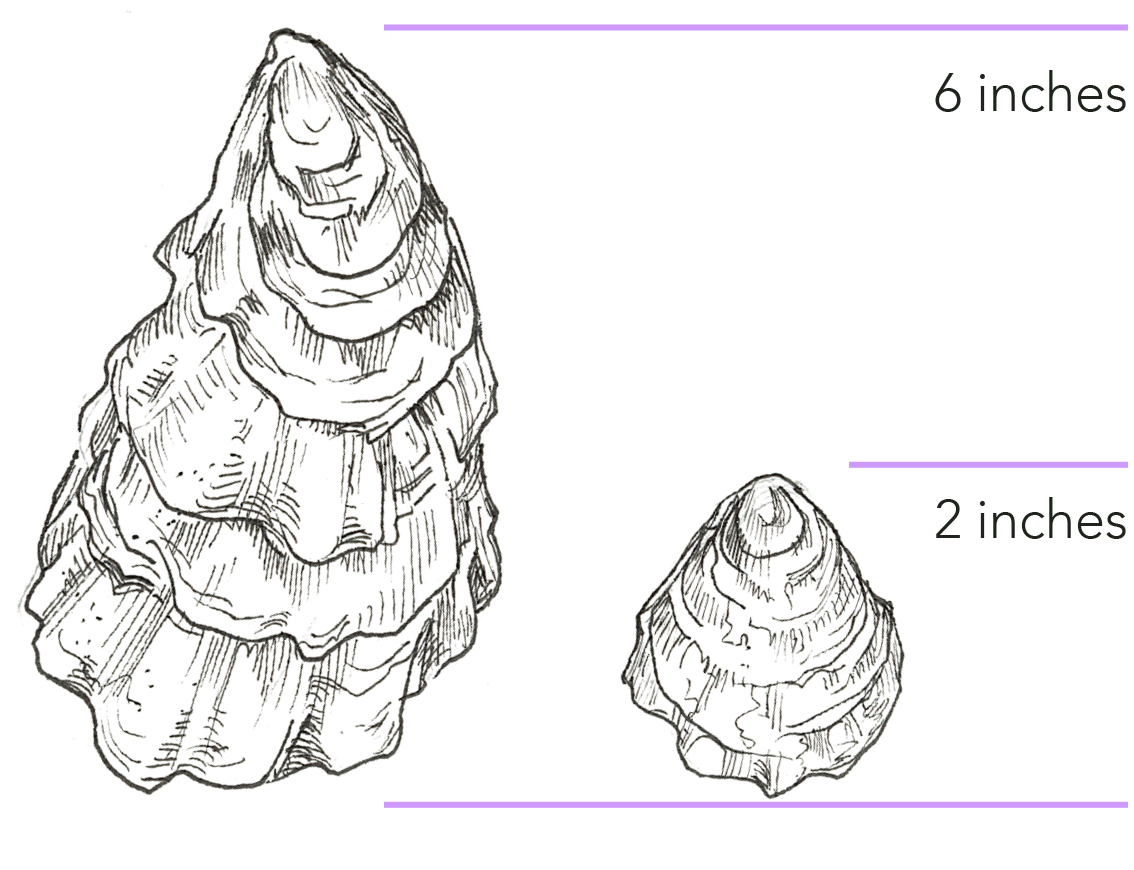

Olys grow slowly. They can spawn at 4-5 months of age but then take years (as quickly as 18 months but as slowly as 4 years) to reach their adult size of 1-2 inches wide. For wild Olympia oysters reproduction will only happen if the water temperature is warm enough. While Olys are at home in the cold Pacific, they generally are found in quieter bays and estuaries where the water temperature will rise above 60°F in the summer or fall to initiate spawning and allow the life cycle to begin again. A recent study noted that climate change and warming oceans may provide a positive boost to Olympia oyster reproduction.