A Muddy Partnership

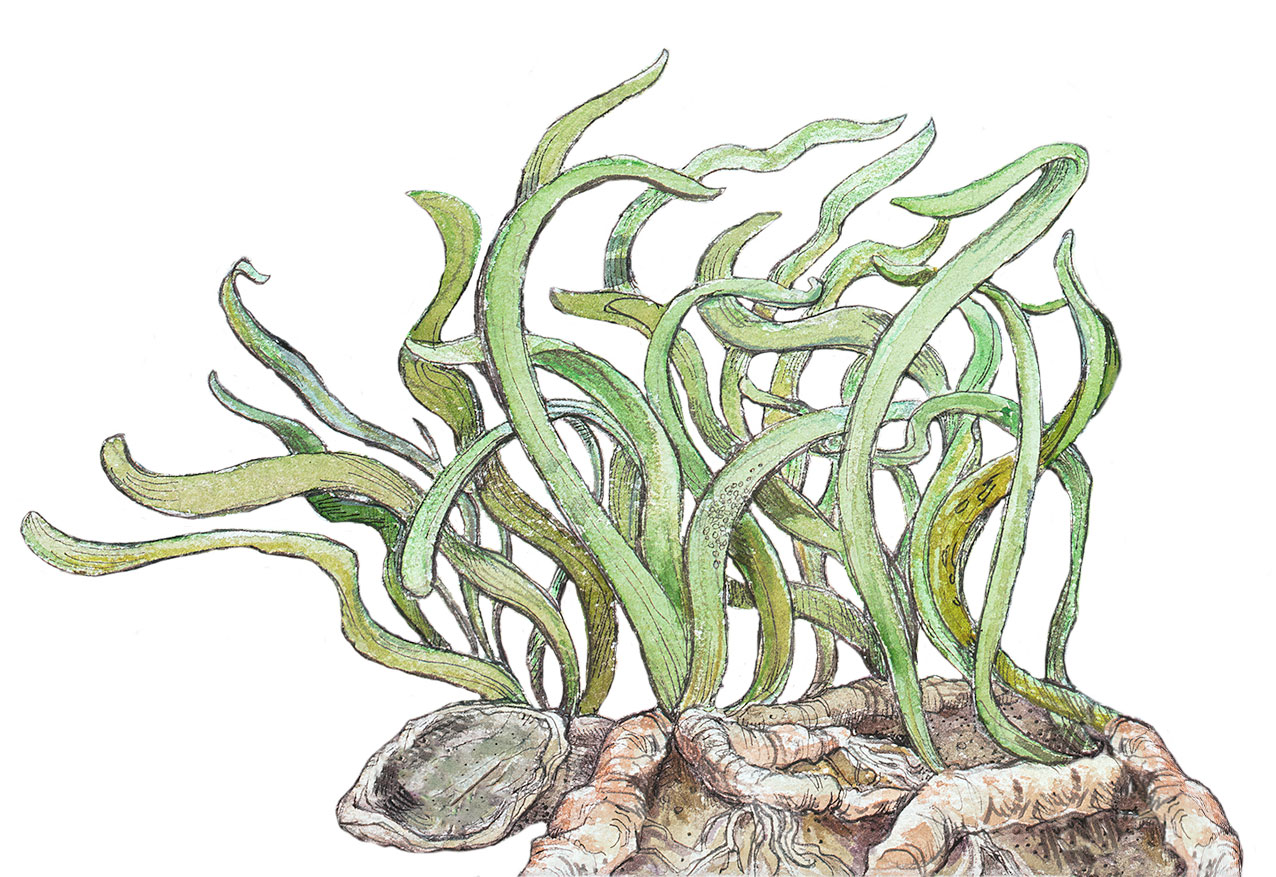

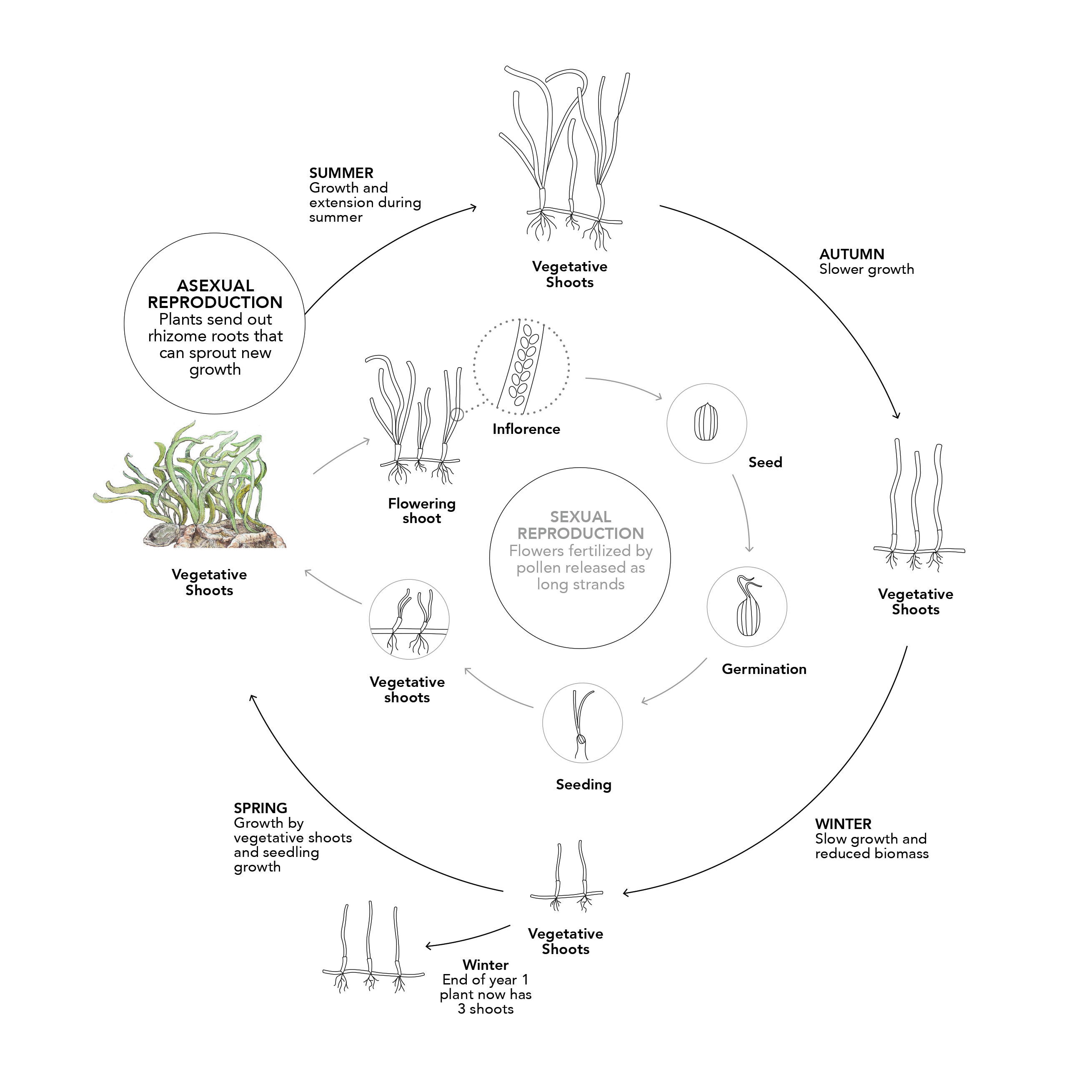

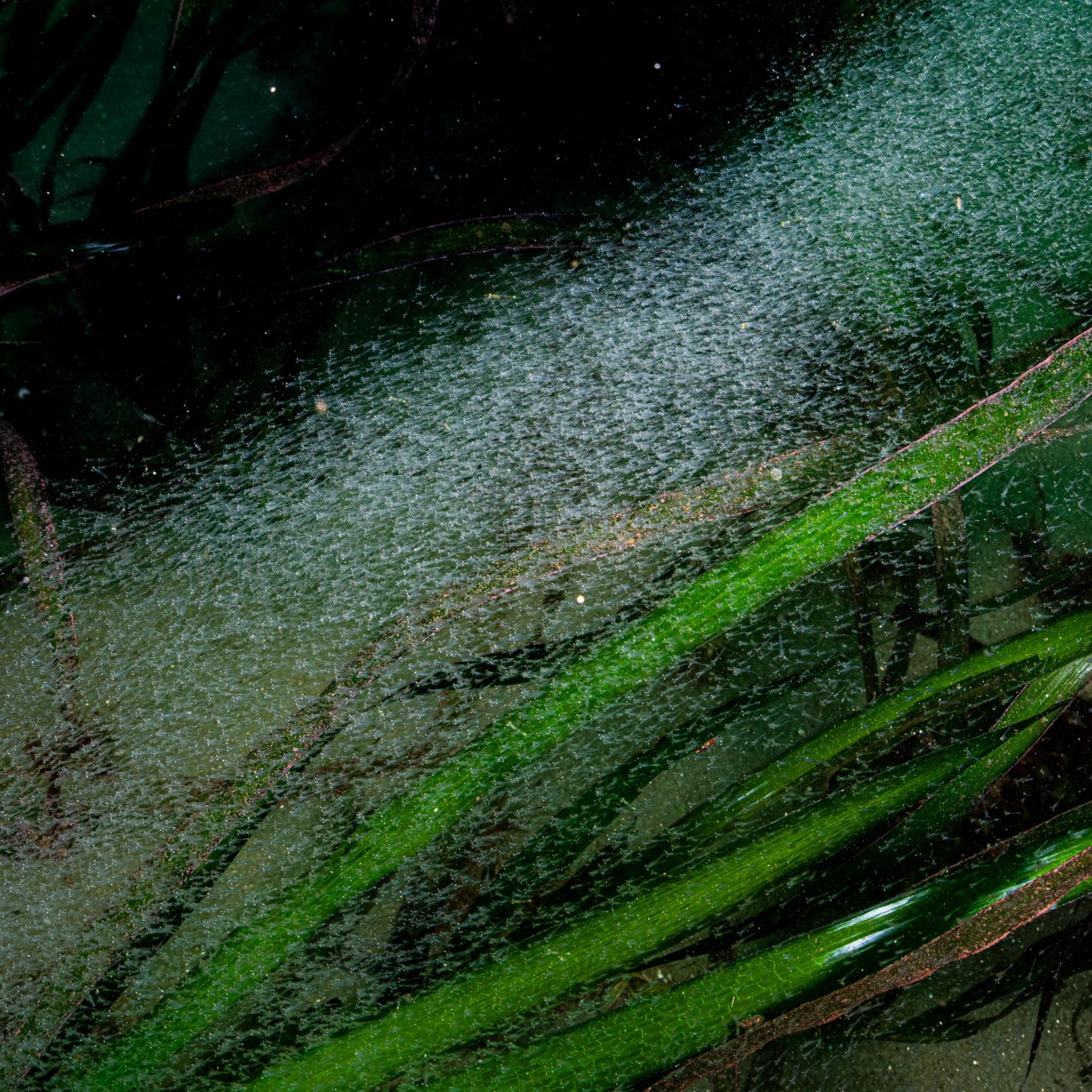

Of the various foundational habitats in an estuary, a few stand out: on the watery side of the ever-shifting shoreline are oyster, seaweed, and eelgrass beds, with salt marshes playing their important role on the drier side of this muddy realm. Eelgrass is often described as an underwater meadow, but many plots of eelgrass in San Francisco Bay are better described as a forest; it grows in patches of tall blades reaching the surface in deeper water, encountered when kayaking or paddleboarding away from shore.