Plant or Animal?

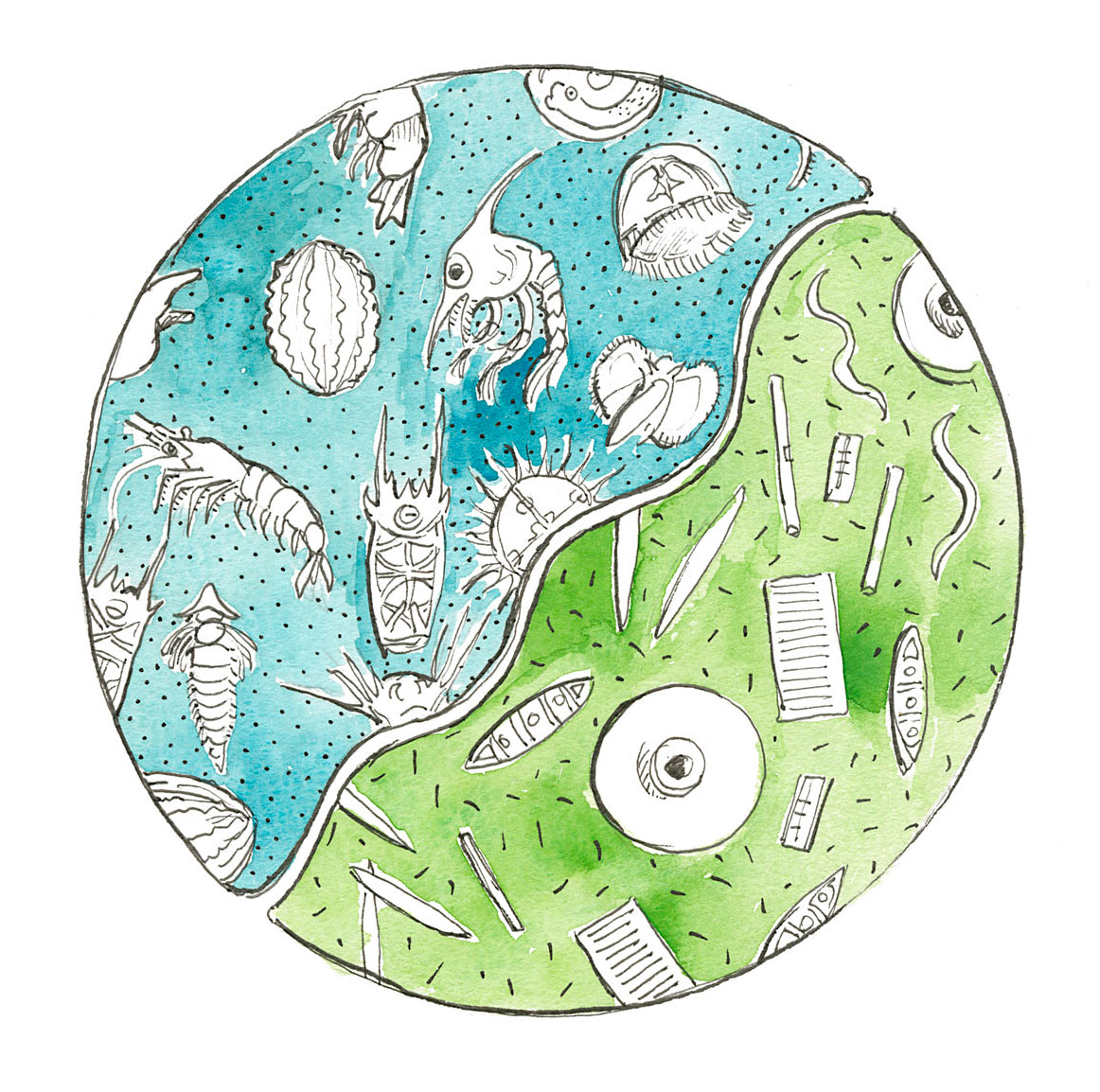

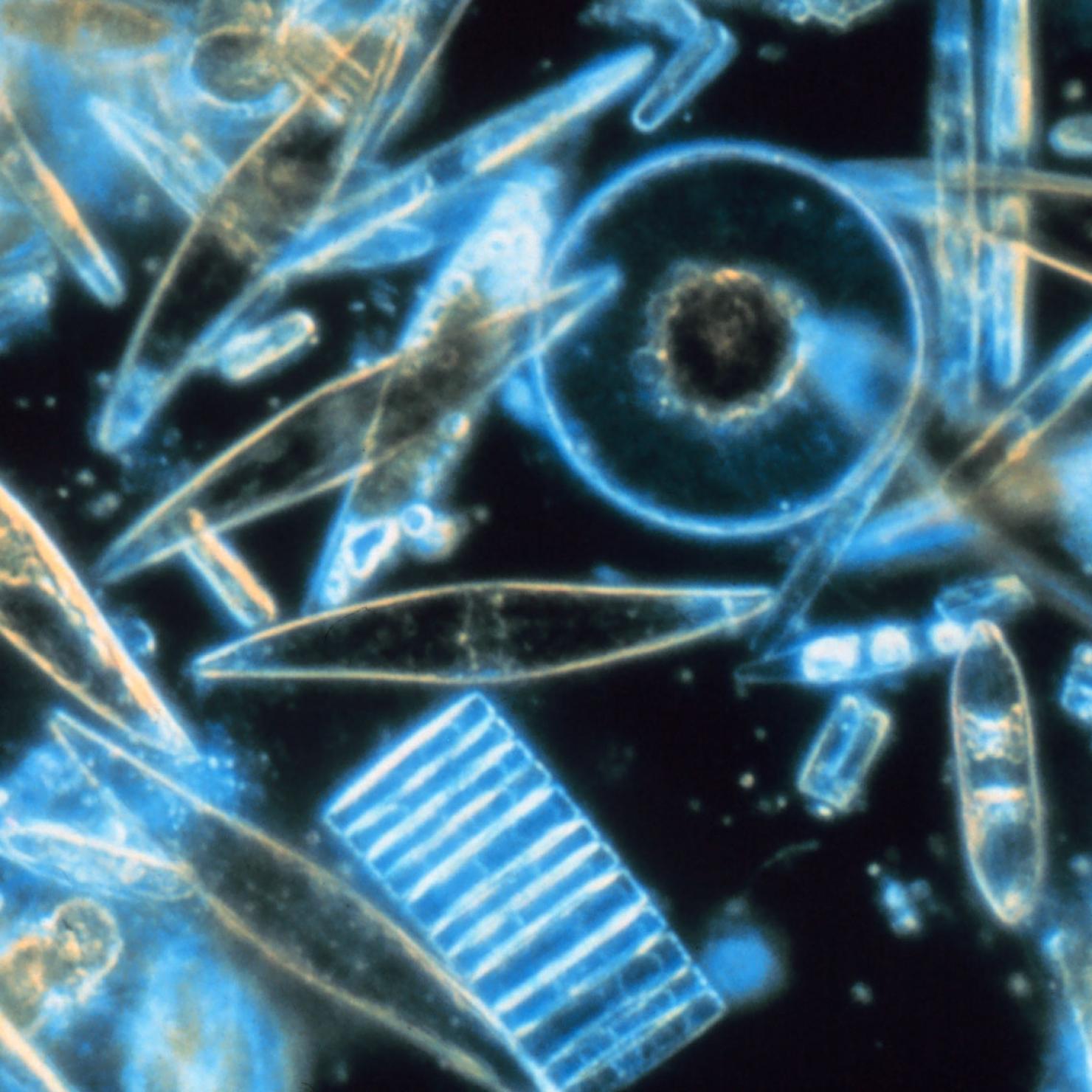

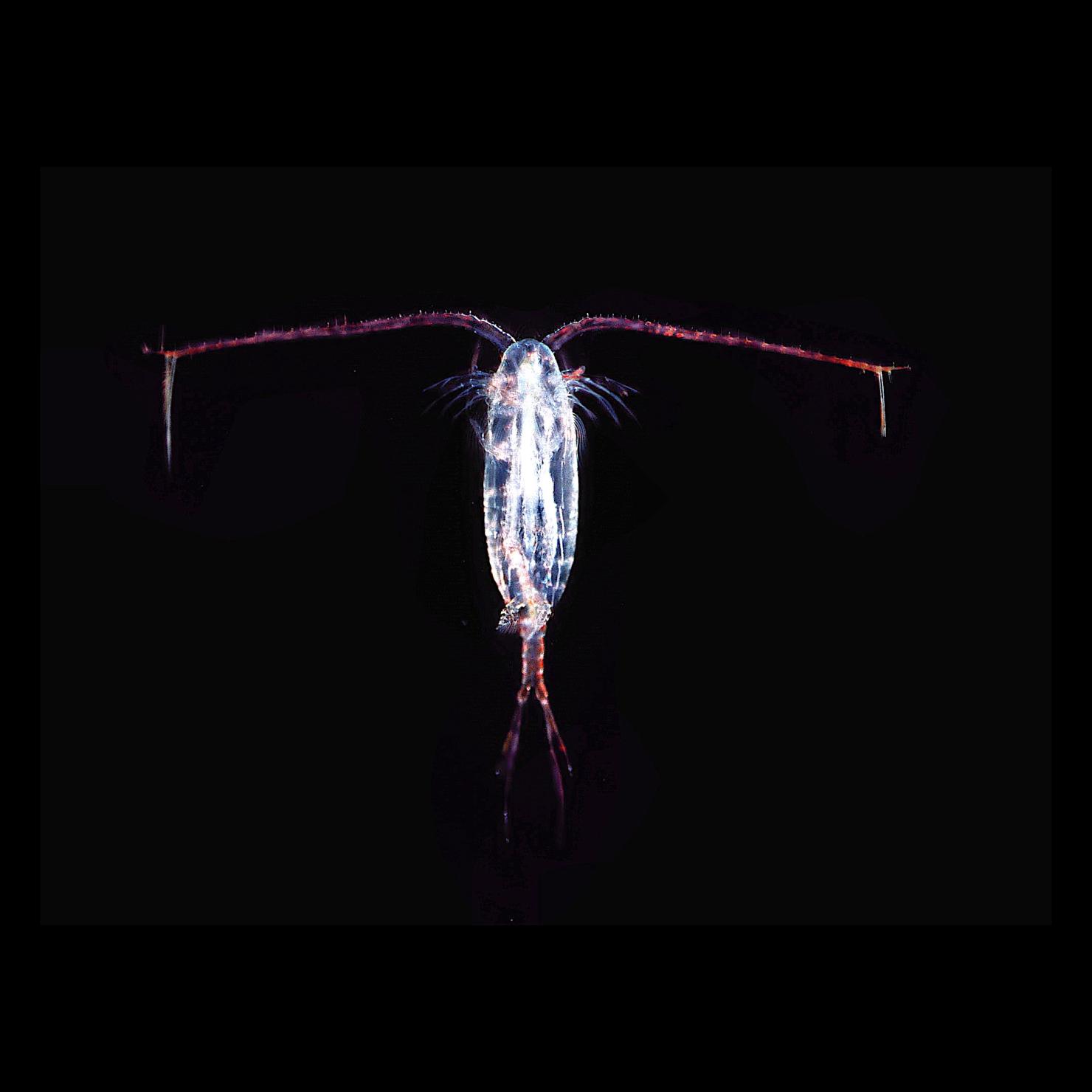

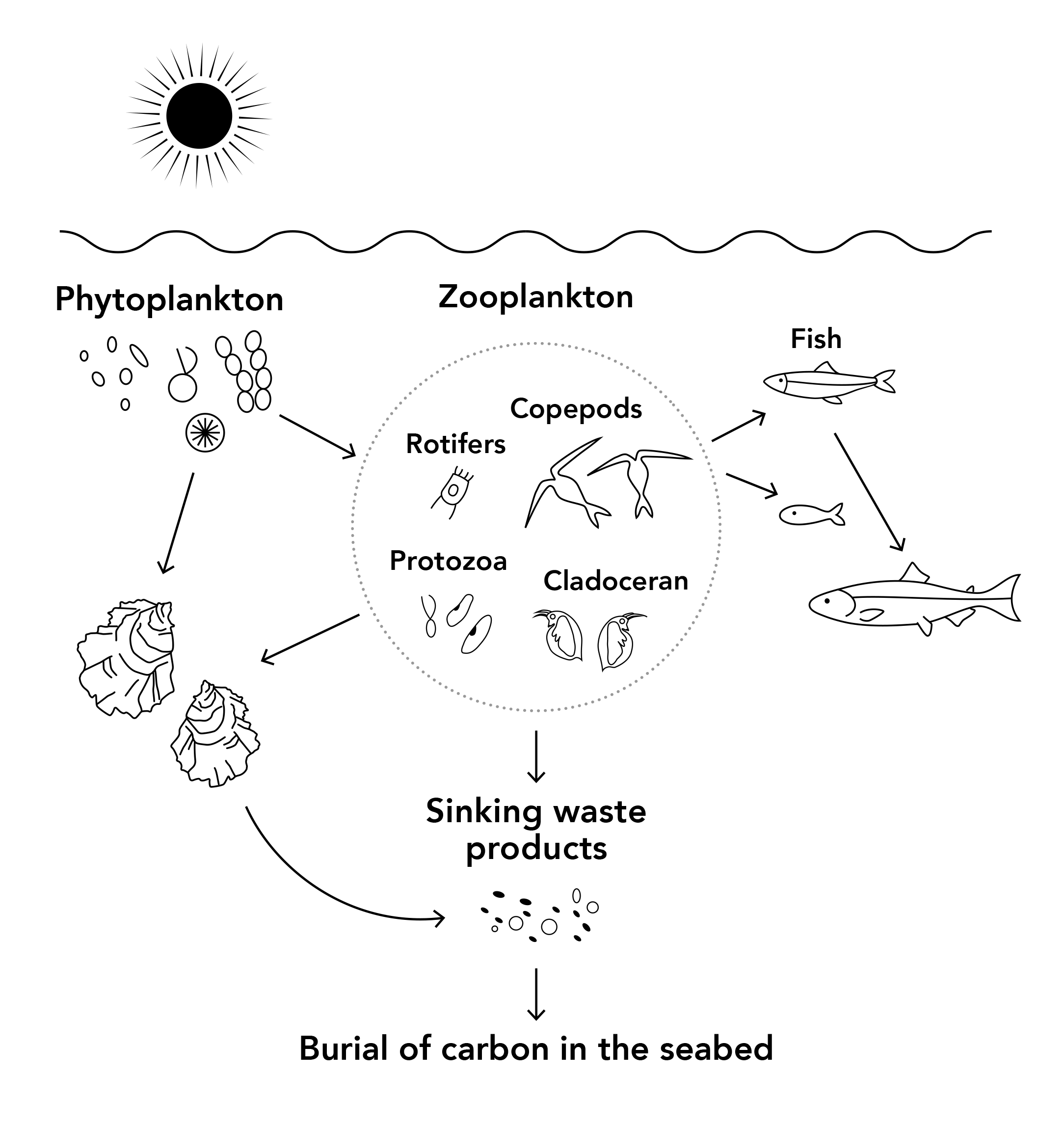

Phytoplankton are single-celled organisms which, like plants, use the energy of the sun and nutrients in the water to create their own food. They are also called single-celled algae. In algae, chlorophyll harnesses sunlight’s energy, and photosynthesis converts CO2 and water into oxygen as a byproduct. The evolution of phytoplankton in the primordial ocean created the oxygenated atmosphere that the rest of life needed to begin evolving, and phytoplankton in oceans, streams, lakes, and estuaries create about half of the oxygen in our atmosphere today. Like a plant fueled by nutrients from the soil, phytoplankton pull nutrients out of the water. These are the minerals washed down from the mountains through the Delta to swirl around in the Bay. Nitrogen and phosphorus are the most important, but trace metals such as iron, manganese, and zinc are also needed. Diatoms are a kind of phytoplankton that live in microscopic glass houses—they need silica to build their complex cell walls.

Phytoplankton, including diatoms, are the basic food source for oysters, other bivalves, and the small juvenile stages of many organisms from invertebrates to fish. An Olympia oyster, glued to its rock or another oyster at the edge of the bay, brings water in through the mantle and over its gills where a mucus layer collects phytoplankton and other particles and funnels these nutrient packets into the mouth and stomach where it is transformed into proteins and carbon, i.e. biomass. The talents of the oyster’s gills are such that it funnels the needed particles of food towards its mouth and stomach while waving the mucus packets of larger, non-digestible particles the other direction and back out into the water.