Foundational Food & Carrier of Culture

Sunset on Puget Sound, 1898

Oysters, other shellfish, and seaweeds have supported the human species since the very beginning. In 1975, the archeological remains of a twelve-thousand-year-old human settlement at Monte Verde in Southern Chile was discovered. Among the artifacts preserved in the peat bogs were the clear remains of nine species of marine algae from distant beaches and estuaries. These seaweed relics, confirm a nutrition highway along which the first humans peopled the coast of North and South America either by boat or along the shore, eating the abundant shellfish and seaweed there. Oysters, clams, seaweed, crab, and fish from the shallow ocean estuaries and beaches of the time (many miles out from today’s shoreline) provided the fatty acids (important omega-3s), iodine, and other minerals essential for human brain development. The complex human brain requires a specific mix of nutrients, especially iodine, to develop as it did—nutrients found only in shellfish, fish, and seaweed.

Mural painting of Huichin Shellmound, Berkeley, February 5, 2017.

Shellmounds as Markers of Place

Clam, mussel, and oyster shells, animal bones, ash, and other relics of reverence, collected over generations by a particular tribe—Miwok in Marin, Rumsen, or Ramaytush Ohlone in other parts of the Bay—into massive accumulations, or shellmounds. These raised features in the landscapes are important markers of place, sacred burial and ceremonial sites, a vestige of villages long ago emptied and replaced by contemporary life, parking lots, and shopping malls.

The sheer enormity of some of the shellmounds, (Emeryville shellmound is estimated to have been a 60 feet high mound with a 350 feet in diameter) is an indicator on dry land of the prodigious productivity of the muddy underwater world along the edges of the bay, a productivity that sustained stability.

“The Ohlone consider the remains of all who lived before to be sacred; whether it is a human or a clam, it is valuable, even sacred. The shells of clams, abalones, oysters, mussels, and cockles are so valuable to the Ohlone — in fact, to all California Indians — that they are still considered precious and valuable. The shells are still sanded, drilled, and lovingly crafted into fine jewelry today, as a reflection of the great value of these important sea creatures. To be buried in shells, even today, would be an incredible honor.”

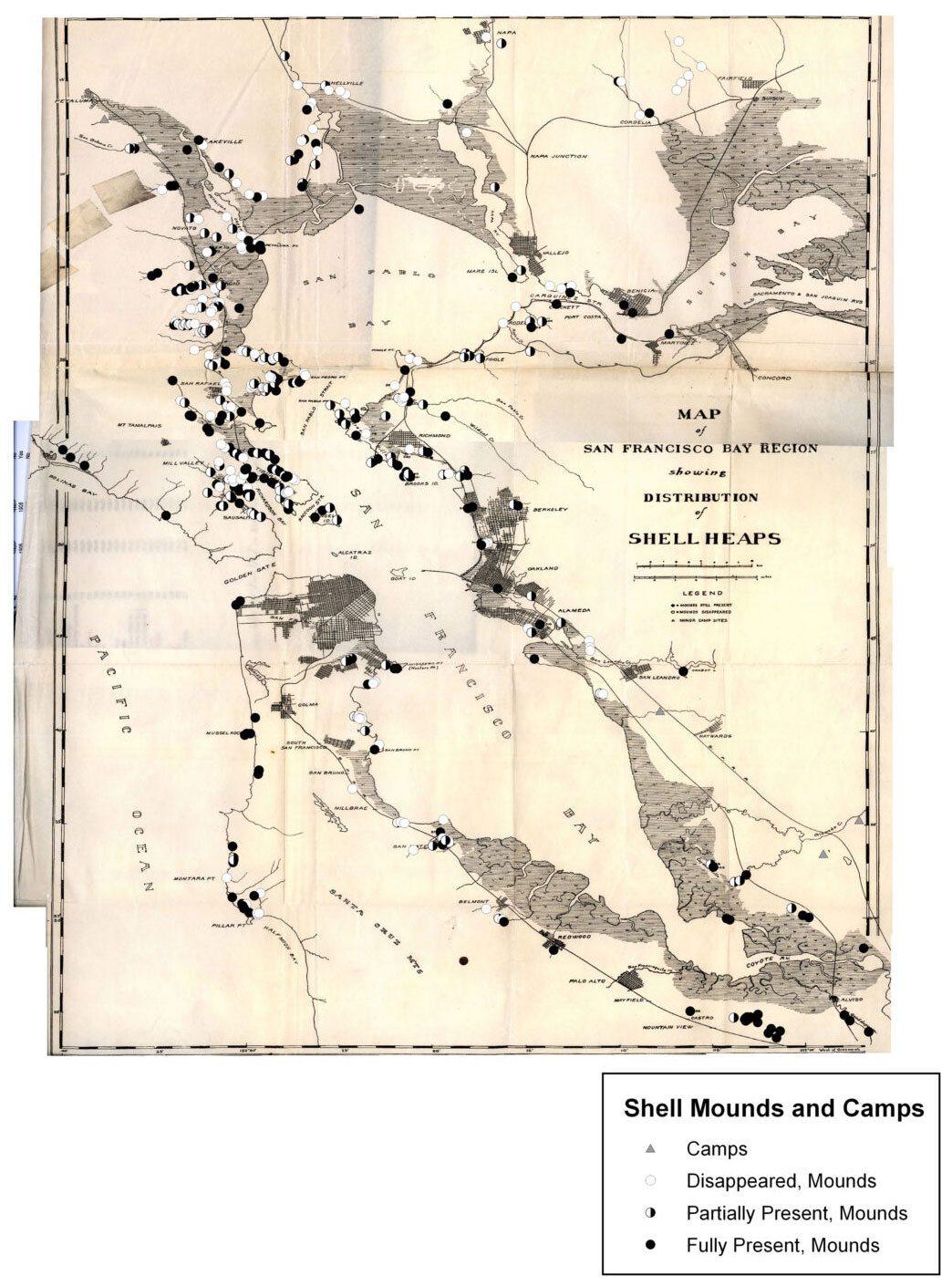

By 1905, the shell mounds were disappearing under the bulldozers and cement paving of contemporary life. Nels C. Nelson, an archaeologist from the University of California, conducted an archaeological survey of the San Francisco Bay Area between 1907 and 1908, documenting the region’s shellmounds. His 1909 map identified 425 shellmounds distributed along the shores of San Francisco, San Pablo, and adjoining bays, though he noted that many had already been destroyed by development or erosion. The composition of the shellmounds has been studied by tribes, archeologists, and others over the years and indicates that clams and mussels were the primary shellfish food source with oysters showing up in fewer numbers. Estimating native oyster abundance in the Bay from this analysis is an ongoing conversation. Tsim Schnieder has studied the shellmounds of Marin in great detail.

Nelson’s map, 1909: 425 shellmounds located, both partially and full present.

“My analysis and comparison of multiple forms of evidence—archeological, ethnographic, and archival—help give shape to a broader landscape that was continually inhabited, memorialized, and rendered meaningful. I see the persistence of time and place in the dusty layers of three unassuming shellmounds.”

“mak-’amham” means “our food” in the Chochenyo language.

“Ohlone would collect shellfish in the area around salt ponds with digging sticks made from either wood (manzanita or oak) or deer bone to pry the oysters from the rocks and mud. They would be collected in burden baskets or trays and prepared a number of ways like being cooked in an underground earthen oven, or strung on a dogbane cord and smoked and then eaten with acorn bread. It was a very refined way of eating oysters and would be part of a grand feast eaten on top of a shellmound.”

Low-brow to high-brow

The evolution of oysters on the West coast from a familiar and favored food of the 19th century to the refined extravagance available at oyster bars of the late 20th century and today, is a history better told in the Pacific Northwest, in Washington State. The abundance of native oysters in Willapa Bay and Puget Sound, the demand for oysters in the population centers of the entire west coast, especially San Francisco, and the ability to ship them there created the environment for an oyster industry that evolved from collecting to cultivating to full-blown commercial oyster farming at a large scale.

The original collectors of Olympia oysters around Southern Puget Sound formed an association dedicated to maintaining the oyster industry over time. When Oly numbers declined, they moved to cultivating Eastern oysters (Crassostrea virginica), and finally to breeding and farming Pacific oysters (Crassostrea gigas), the large, meaty oysters first brought to Puget Sound from Japan in 1919. The Pacific oyster became, and has been since, the commercial oyster of choice for farmers, chefs, and oystershuckers throughout the Pacific coast. The creation of oyster hatcheries, where oysters are prompted to spawn in tanks and their larvae captured and cultched onto tiny shells to be shipped to oyster growers around the world, has amplified oyster farming into the contemporary aquaculture industry of today. Native Olympia oysters—small and slow to mature—are grown by some oyster farms as a specialty, heritage oyster to be tasted and celebrated when the anticipated harvest comes. The Oly taste is distinctive; immediately identifiable no matter where they are grown!

“This delicious article of food has become so necessary with every class of the population that scarcely a town in the whole country can be found without its regular supply. By means of railroads and water channels, oysters in the shell, or out of the shell, preserved in ice, in pickle, or canned, are carried even to the remotest parts of the United States.”

Still Life With Oysters, Fruit and Glasses on a Table

Aquaculture specialist: Hog Island Oyster Farm runs a hatchery in Humboldt Bay where oysters are spawned and larvae raised until they are spat, tiny oysters attached to tiny pieces of shell.

Oyster Farmers as Stewards and Scientists

The oyster growers’ intense intimacy with the waters in which their oysters grow has made them forceful advocates for water quality protections. Taylor Shellfish in Washington and Hog Island Oysters in Tomales Bay have become invaluable partners in stewardship and research, working with state environmental agencies and the scientific community to tackle questions about the relationships between oysters, eelgrass, seaweed, kelp, ocean acidification, and other issues affecting our waterways. “It’s about business solving environmental problems, not creating them,” explains Terry Sawyer, co-founder of Hog Island Oyster Company on Tomales Bay, north of San Francisco.

Oyster farmers are also effective messengers for eating sustainably grown, super-healthy protein. Oysters need no fresh water, use no fertilizer, and are a benefit to the waters around them. While we wish we could be harvesting wild oysters from the shore at low tide, for now we can be eating oysters from the farms, not from the mudflats.

Olys on riprap at Heron’s Head Park, San Francisco.

Why Can’t We Eat Olys from the Bay?

Olympia oysters in San Francisco Bay were nearly wiped out by overharvesting, shoreline development, and industrial pollution during and after the Gold Rush. No commercial oystering has happened in San Francisco Bay since 1930 and today, pollution and high contaminant levels in Bay sediments still make Olympia oysters unsafe to eat, even though scattered populations can be found. Farmed native or Pacific oysters, by contrast, are grown in clean coastal waters under controlled aquaculture conditions; the Pacific oysters grow larger and faster than Olympias and have a mild, sweet flavor. While Olympia oysters in San Francisco Bay play an important ecological role their slow growth and uptake of pollution make them unsuitable for any kind of wild harvest or foraging. Someday, we hope the Bay waters will be clean enough and the Oly populations robust enough for our grandchildren to collect native oysters at the shoreline to enjoy on an evening with friends and family.

Hog Island Sweetwaters, Pacific Oysters from Hog Island Oyster Co.

Eat an Oyster, Restore an Oly

An Experiment in Recycling

Eating oysters at the Ferry Building or while waiting for a ferry at Larkspur Landing or on the edge of Tomales Bay overlooking the Hog Island Oyster Farm, is a quintessential experience of place that permeates all one’s senses, especially as the mouth and body are invigorated by the entry of the oysters themselves. Heaven! But it is time for all of those enjoying a taste of place to become aware of the original oyster of this place, the Olympia oyster, Ostrea lurida.

A new program recycling the Pacific oyster shells from Hog Island Oyster bars into cultch used to cultivate and promote the growth and resilience of the Olympia oyster in the Bay will help make that connection.

“While Pacific oysters offer you a variety of tastes—merroir if you will, or the specific taste of place—an Olympia oyster always tastes like an Olympia oyster, distinct and most certainly itself.”