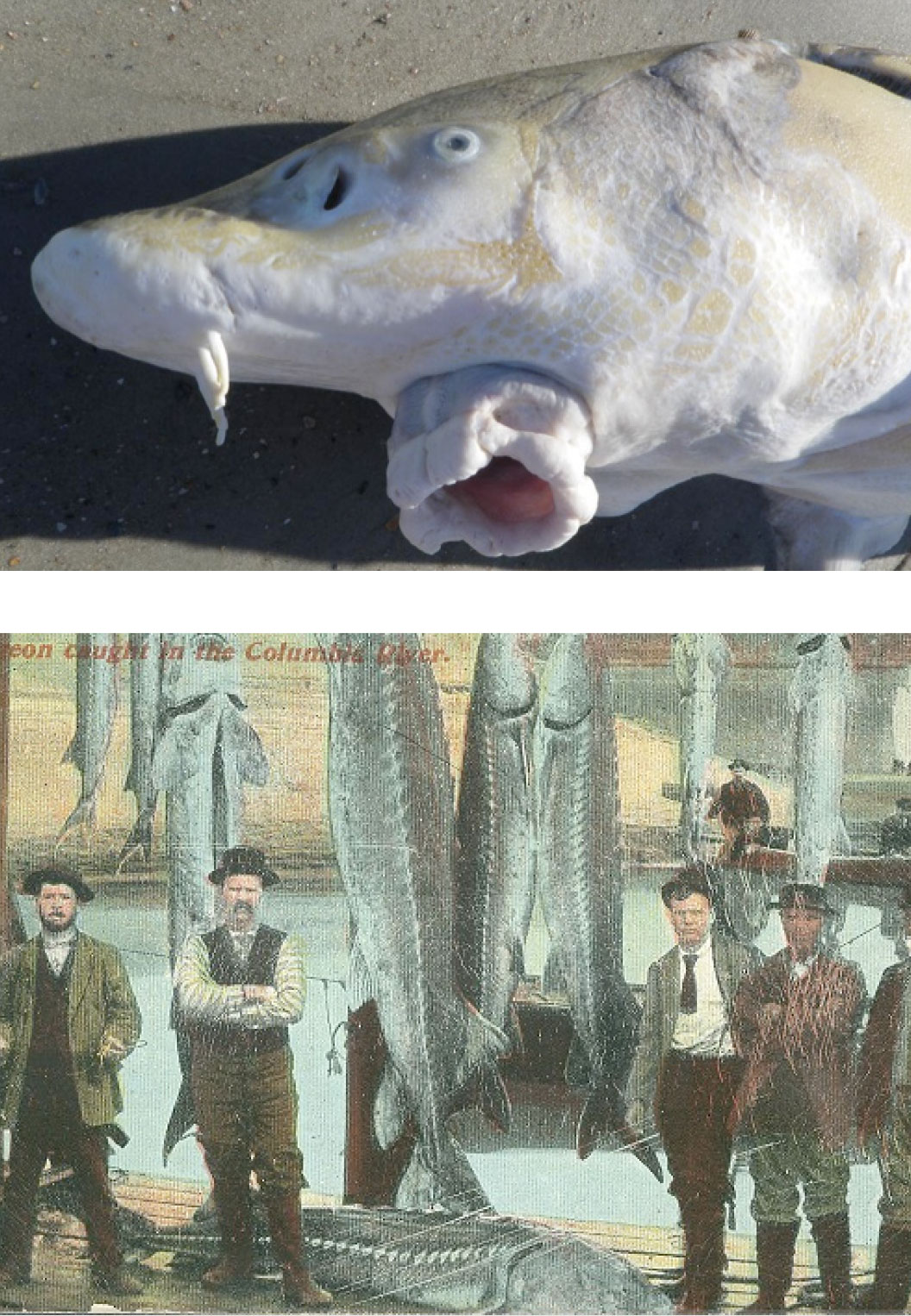

Sturgeon have also been a startling indicator of the deadly effects of harmful algal blooms or HABs. HABs occur when too many nutrients, often from agricultural run-off, cause an explosion of phytoplankton. Toxins can be directly associated with the overpopulation of algae, but it is the mass of bacteria that eat the mats of algae that suck up all the oxygen in surrounding waters, leaving none for other fish and animals to breathe. In the summer of 2022, an enormous bloom of a particular phytoplankton, Heterosigma akashiwo, reduced oxygen levels throughout the San Francisco Bay, causing mass fish die-offs and particularly impacting sturgeon. Almost 700 sturgeon carcasses, both green and white, were documented by citizen science surveys and iNaturalist reports (and analyzed by sturgeon researchers) from the southern tip of the South Bay, through the Central Bay, and all over San Pablo Bay in the north. Before the reordering of the bay and delta by agriculture and people, when native oysters covered the bottom of the bay, and along the margins, their millions of gills sieved water for nutrient algae, helping maintain the balance between phototrophs and all the creatures needing to breathe oxygen in the water.

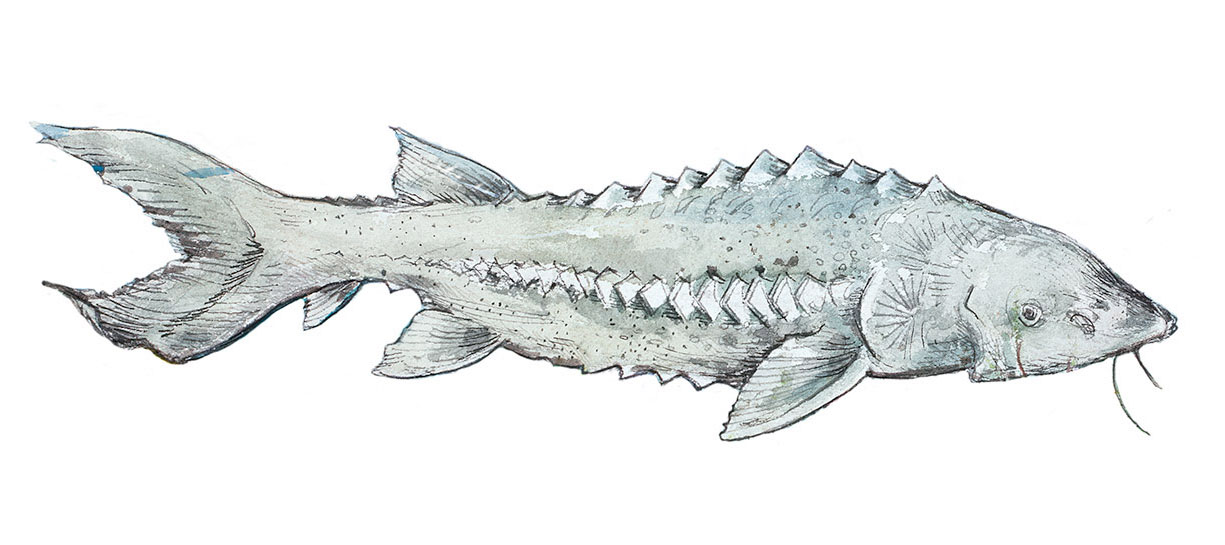

Sturgeon can grow to be 80 years old, spawning only every few years, so a mass die-off is tragic for this long-lived, prehistoric, scaleless fish that can emerge from the dim bottom of the bay in athletic jumps at the surface. Acknowledging their presence in our local waters, alongside the Olympia oyster, can be a wake-up call to restore water flows, and manage pollution levels, around the Bay so their cycles of life can again flourish.