Crabs in the Bay

There are at least twenty kinds of crabs crawling along the bottom of San Francisco Bay, but three of them stand out as significant in the Olympia oyster’s world.

There are at least twenty kinds of crabs crawling along the bottom of San Francisco Bay, but three of them stand out as significant in the Olympia oyster’s world.

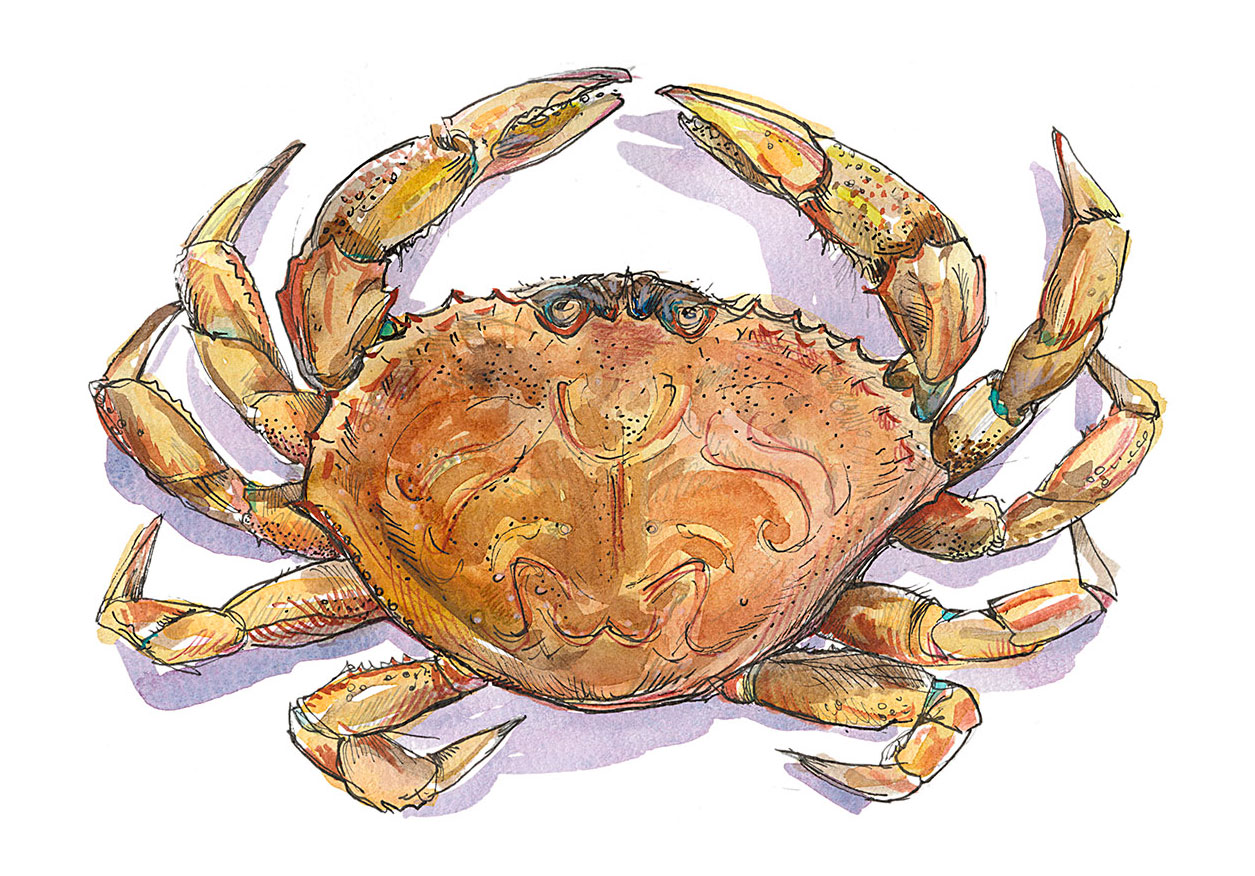

Dungeness Crab

Metacarcinus magister

Dungeness crab (Metacarcinus magister) support significant commercial and recreational fisheries. The crabs caught offshore by boats from ports such as Bodega Bay and Half Moon Bay have had a long journey along the seafloor from San Francisco Bay, where they are fully protected. No take of any kind is permitted in San Francisco Bay and San Pablo Bay. These rich estuarine waters, especially the warmer, sandy bottom of San Pablo Bay, is the Dungeness crab’s nursery, providing important habitat for these crabs during key stages of their life cycle.

A cluster of Olympia oysters is a safe resting niche for a small crab. Can you find it?

Dungeness crabs float into the Bay as larvae (riding the tides or hitchhiking on jellyfish), and grow in sand beds and nearshore shoals, and amongst the eelgrass and Olympia oyster beds along the shores. The crab larvae eat plankton then small fish and smaller crustaceans (even smaller crabs), molt almost twelve times as they enlarge, progress out to deeper water and then, as teenagers (now almost four inches wide) march along the sand dunes of the bottom of the Bay, out the Golden Gate to the open ocean where they will grow to adulthood. Twenty miles from San Pablo Bay out to the Greater Farallones Marine sanctuary for a crab would be like you or I walking from San Francisco to San Diego. Dungeness crabs that mature in San Francisco Bay grow faster than anywhere else on the Pacific Coast.

This robust nutritional uptake for Dungeness crabs is a testament to the fecund worlds that Olympia oysters and eelgrass are a part of in the Bay. The mix of nutrients whirling from ocean and river sources, the extraordinary melange of zooplankton and small isopods and amphipods in and around the oysters and eelgrass for young crab to eat, the sandy bottom created when sediment is held in place, all combine to make an ideal crab playground to grow up in. Olympia oysters also create perfect places for a young crab to hide. A bed of Olys will offer the right-sized crack to hide in, camouflaged from larger predators.

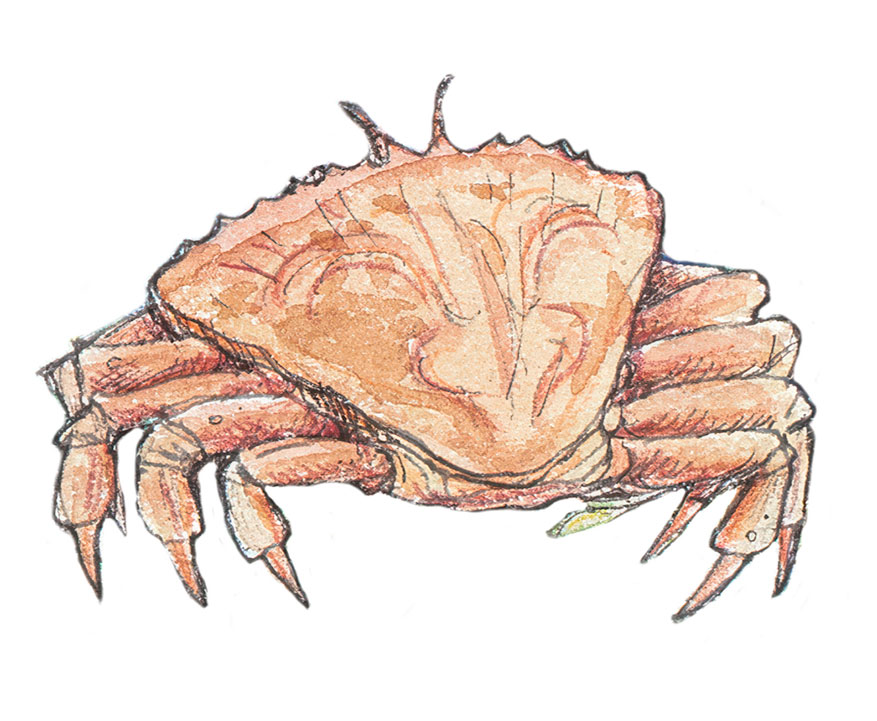

Rock Crab

Cancer spp.

Rock crabs (Cancer spp.)—including brown, red, and yellow species—are also abundant in San Francisco Bay. They are adapted to rocky, reef-like habitats and hard-bottom substrates commonly found along the jetties, breakwaters, and natural rocky outcrops around the Bay’s edge. They are more often found in shallower waters than Dungeness crabs and frequently occupy intertidal to subtidal zones, sometimes even tolerating lower salinities but generally avoiding deep, muddy channels. Their strong claws, with the telltale dark-tipped pincers, and thicker shells are adaptations for prying open hard-shelled prey, like snails, clams, barnacles, and oysters, and anchoring themselves among rocks, where they remain well-camouflaged and protected from predators.

Like other crabs, mating can only happen when the rock crab females are molting. A sperm packet is left by the male inside the female crab, eventually fertilizing her eggs that she carries under her abdomen as they develop. A female rock crab might hold as many as 4 million eggs that she releases as larvae six to eight weeks later. The larvae go through seven developmental molts before settling onto the ocean bottom as tiny crabs. Only a small portion of these become crabs; the rest add to the nutritional subsidies of the rich stew that is the shallow-water zone

around the Bay.

Green Crab

Carcinus maenas

Green crab (Carcinus maenas) are the notorious invasive crabs native to Europe, that have taken over waterways around the world, but most drastically on the east coast and the west coast of North America and southern Australia. Transported initially in bait boxes, green crabs are proving almost impossible to eradicate. They reproduce efficiently, and their larvae can drift long distances to spread populations across an extended coastline. Their destructive habits are many.

A juvenile C. maenas showing the common green colour

They are voracious eaters and efficient predators of juvenile oysters, mussels, and clams, and other native crabs, able to eat over forty small clams in a day. When foraging, they slice through eelgrass at its base, the vital meristem, or point of growth for Zostera marina, thus killing it. This is a distinction from Brant’s geese that forage at the tops of the blades of eelgrass, leaving the meristem below undisturbed to continue growing.

Oyster restoration projects in San Francisco Bay have, to date, not seen significant increase in green crabs or other non-native species. An oddly welcome aside.

Effort to eradicate green crabs have been downgraded to simply trying to keep them in control, but The Smithsonian Institute has an invasives team that has been tracking invasive species in the Bay since 2000. Their mission is:

“…to track the pulse of biotic change in the estuaries and coastlines along the Pacific Coast of North America and to develop new ways of conserving our increasingly urbanized shorelines. We identify non-native species in San Francisco Bay and surrounding coastlines, from Alaska to Panama, learn how their life cycles work in these new environs, and determine what effects they might be having on resident communities. We aim to make the consequences of moving species to strange new oceans both known and predictable, and to understand how these species will interact with changing climate regimes.”

— Smithsonian Environmental Research Center

Note the telltale five spines of the sawtoothed carapace of the green crab. A Dungeness crab has ten.