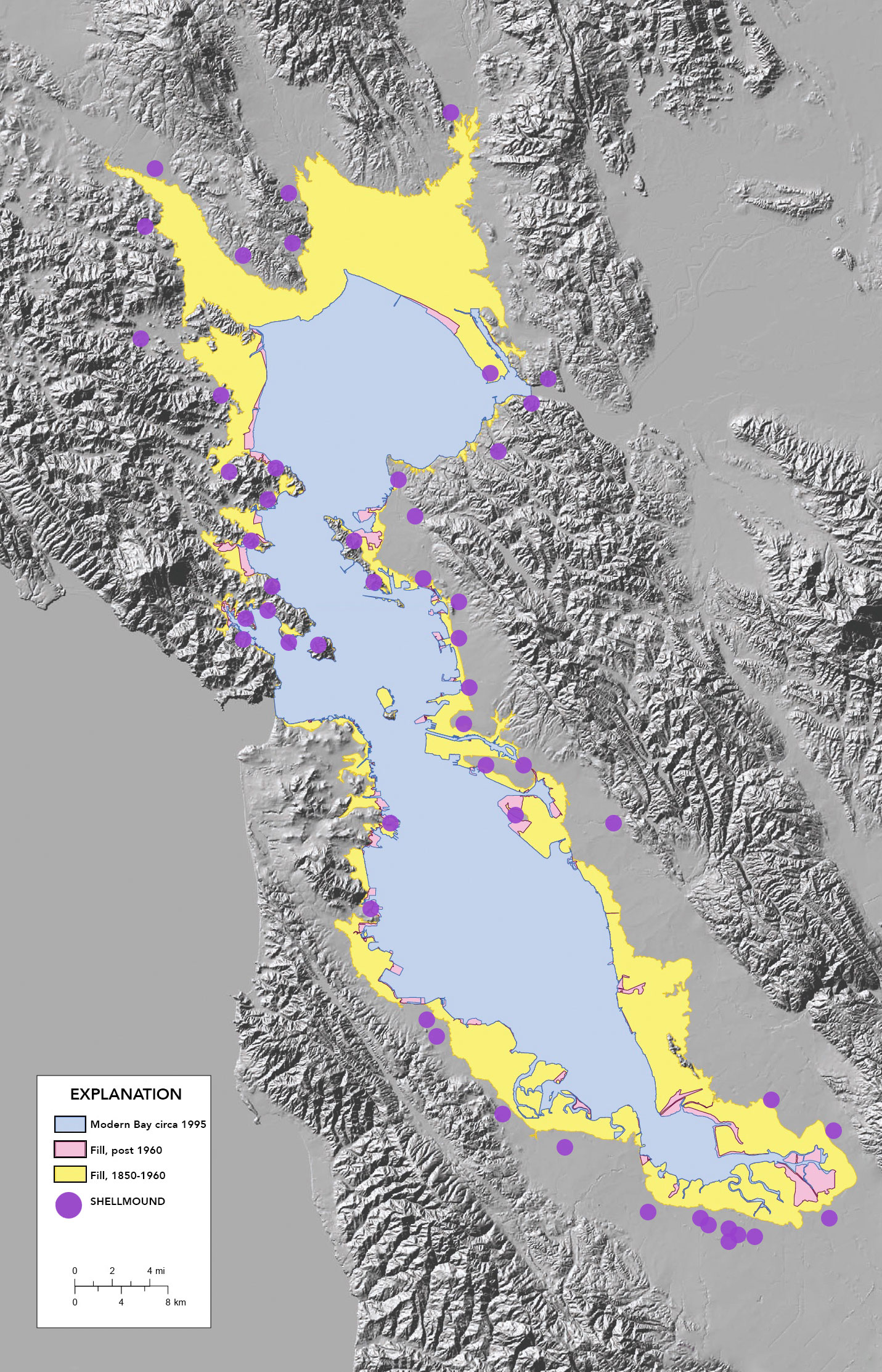

Pollution and Oysters

In 1915, a doctor in Connecticut linked oysters to the transmission of typhoid fever. From that point on, oysters are recognized as a barometer of the waters they are from. Through the 1920s, as human waste was discharged into the local waterways around San Francisco Bay making them a source of disease, people turned away from eating clams, mussels, and oysters. Though the Olympia oyster was not part of the San Francisco oyster industry that shut down by 1930 (it was Eastern oysters being raised and harvested), pollution was affecting its hidden population.

In 1963, the California Fish and Wildlife Department issued a comprehensive study of the California oyster industry that included robust information about the Olympia oyster alongside the Eastern oyster and the Pacific oyster. It states, “pollution can affect oysters in three principal ways: direct poisoning; smothering by sludge; or raising the coliform bacteria count to where there is danger of typhoid and paratyphoid infection of consumers. Domestic sewage is usually the source of the latter contamination, which does not necessarily affect the oyster itself. Industrial pollutants often contain substances that are toxic to oysters, either immediately or after continued exposure. Pollutants may, by combining with the oxygen in the water, lower the oxygen content below that necessary to sustain marine fauna.”

It is hard to know the specific effect of pollution today on Oly populations. While efforts are ongoing to clean the bay, surveys of toxins in fish and other wildlife still register high levels, suggesting that Olys are also accumulating pollution in their tissue. Olympia oyster restoration in San Francisco Bay is, therefore, not for human consumption, but because these little oysters are a superb first responder working alongside myriad human efforts to heal the Bay and rebuild its resilience into the future.