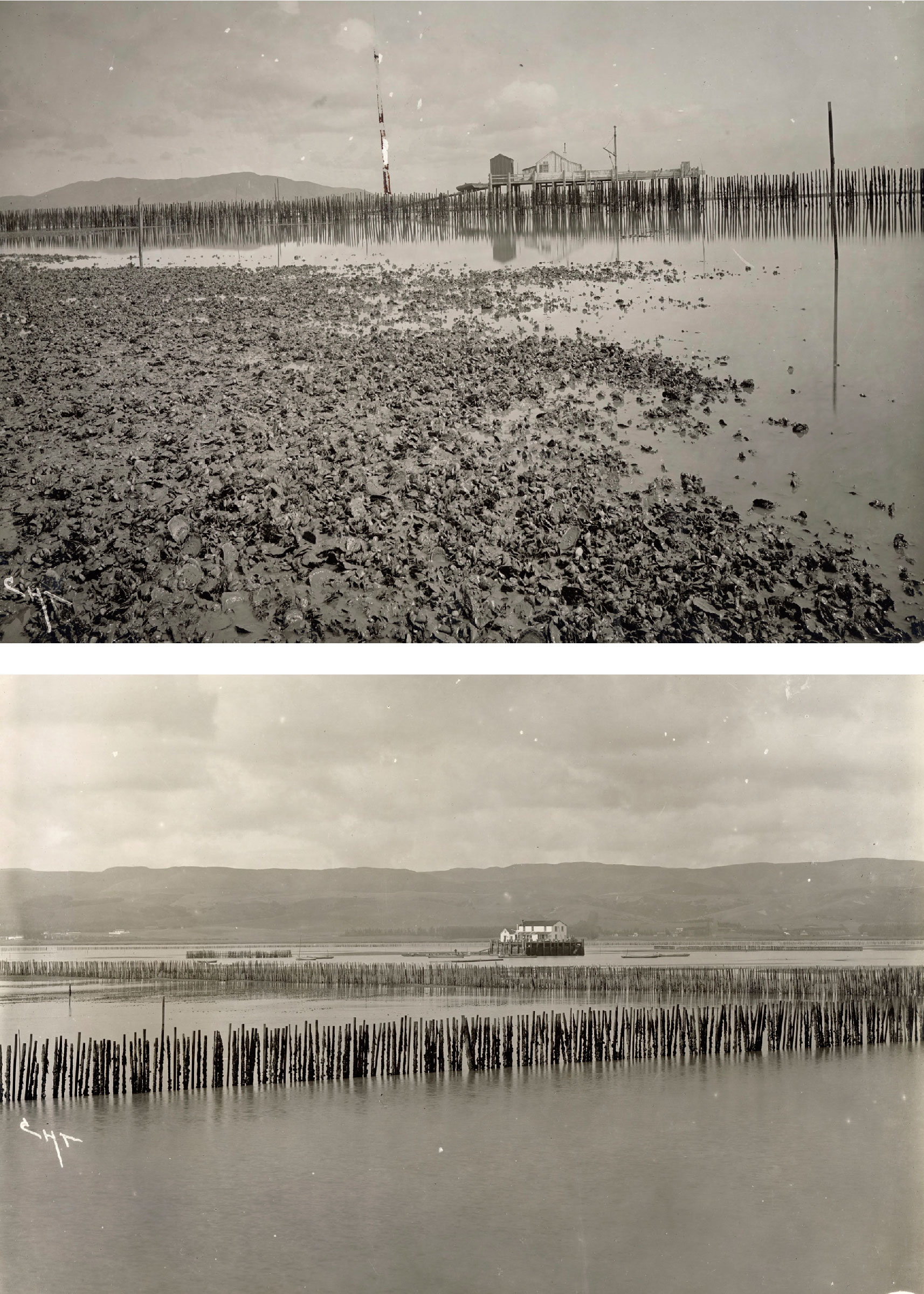

These fences were not only to mark the farm limits of a particular oyster proprietor, thus privatizing what had been common spaces open to all, they were also necessary to keep out a prime oyster predator, the bat ray.Nineteenth-century oystermen reported that rays could destroy several acres of their oysters within a short time.

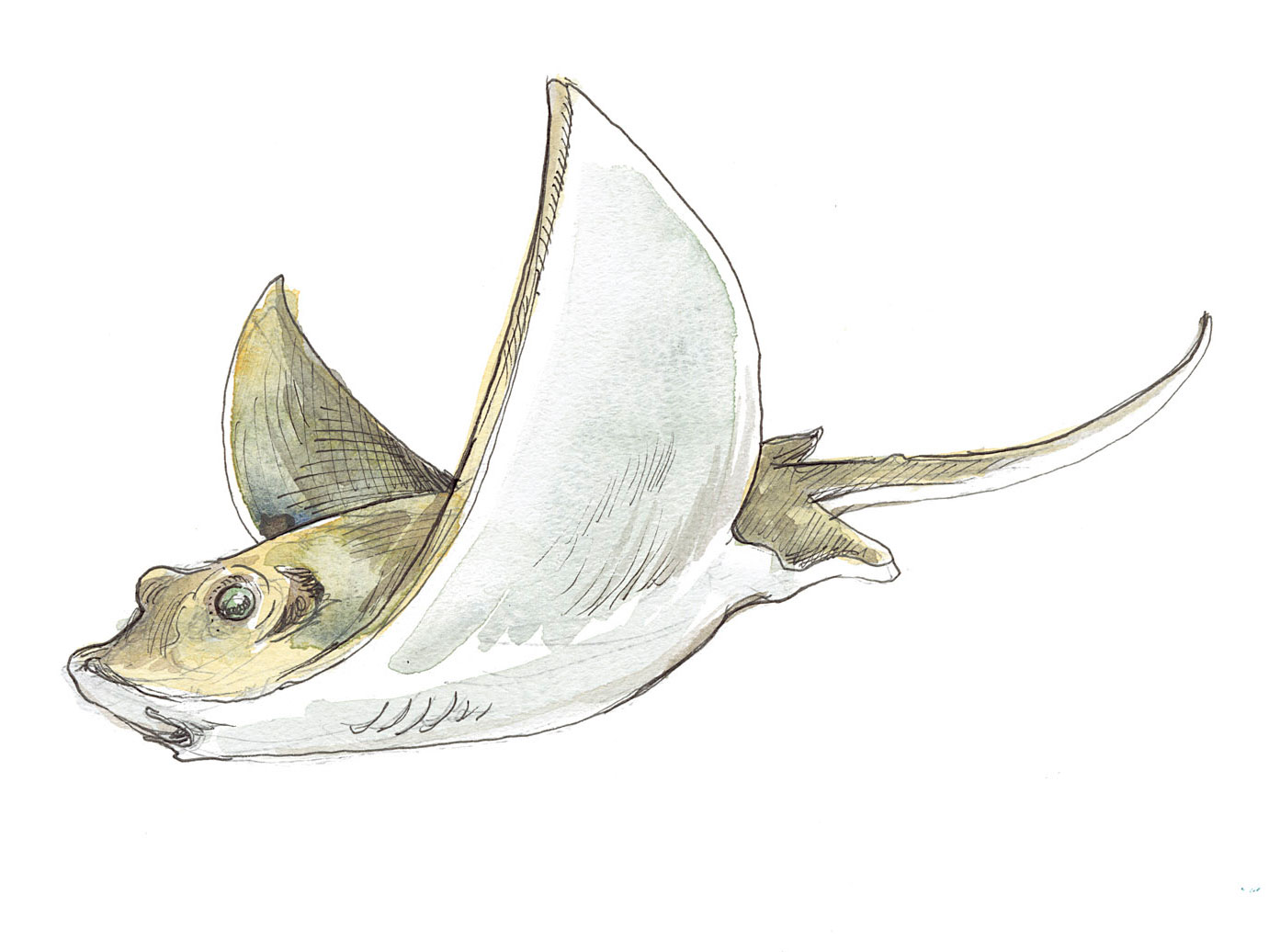

Bat rays are common in San Francisco Bay today. They enter protected bays in large numbers in early spring to bear their young—a mature female can give birth to 10-12 pups—and they remain until fall. The adults are large, often 3 to 4 feet wide, and they weigh as much as 150 pounds. Oysters, if available, can be a chief element to a bat ray’s diet. Bat rays have heavy, flat teeth arranged in a sort of pavement in each jaw. With these teeth they crush the oyster shells and devour the meat.